- Home

- Daniel Mills

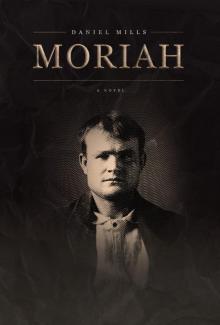

Moriah

Moriah Read online

PRAISE FOR DANIEL MILLS

“Mills deftly jumps between narratives as [Moriah] unfolds, his prose saturating every page with dread as he teases out his characters’ secrets and lies.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Another stunningly twisted tale mired in history from a master of the macabre.”

—Booklist

“[Mills’s] trademark devotion to character, setting, atmosphere, and creeping dread is obvious . . . a slow burn novel immersed in the thick, claustrophobic atmosphere of a dark dream from which there is no waking up.”

—Rue Morgue Magazine

“Daniel Mills is a modern master of the unspoken, a classical horror miniaturist whose writing references the bleak and existentially dread-full gothic Americana of Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Best read out loud around a failing fire on a darksome plain, as night sets in.”

—Gemma Files, Shirley Jackson award-winning author of Experimental Film

“[The Revenants] is an atmospheric, pensive, and impressive debut novel.”

—Paul Tremblay, author of A Head Full of Ghosts

“[The Revenants] is a powerful and compelling novel of colonial America, one which has about it the feel of the genuinely weird and mysterious. . . . Daniel Mills is a writer to watch.”

—Black Static Magazine

“Though these stories bear the influence of Hawthorne, Lovecraft, and Palliser, the numinous dread that fills them is his alone. Mills recalls to us America’s own Dark Wood, and it is lovely to behold.”

—Nathan Ballingrud, author of North American Lake Monsters

“These stories inhabit the modes of the past as a means of approaching a profound darkness, one physical and metaphysical. A pleasure to read, Daniel Mills’s fiction would draw approving nods from any of the austere presences in whose literary footsteps he is following.”

—John Langan, author of The Fisherman

“Mills has a poetic and visionary style of his own, capable of uncovering the beauty in horror and the horror in beauty… a significant and sophisticated contribution to modern weird fiction.”

—Reggie Oliver, Wormwood

Moriah © 2017 by Daniel Mills

Cover artwork © 2017 by Erik Mohr

Cover design © 2017 by Samantha Beiko

Interior design © 2017 by Jared Shapiro

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Distributed in Canada by

Publishers Group Canada

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300

Toronto, Ontario, M6J 2S1

Toll Free: 800-747-8147

e-mail: [email protected]

Distributed in the U.S. by

Consortium Book Sales & Distribution

34 Thirteenth Avenue, NE, Suite 101

Minneapolis, MN 55413

Phone: (612) 746-2600

e-mail: [email protected]

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Mills, Daniel (Horror fiction writer), author

Moriah / Daniel Mills.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77148-413-8 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77148-414-5 (PDF)

I. Title.

PS3613.I5666M67 2017 813’.6 C2016-907553-2

C2016-907554-0

CHIZINE PUBLICATIONS

Peterborough, Canada

www.chizinepub.com

[email protected]

Edited by Samantha Beiko

Proofread by Leigh Teetzel

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

Published with the generous assistance of the Ontario Arts Council.

“These things are true, and I know them to be so, with as much certainty as eyes and ears can give me; and until I can be persuaded that my senses all deceive me about their proper objects, and by that persuasion deprive me of the strongest inducement to believe the Christian religion, I must and will assert that the things contained in this paper are true.”

—The Rev. John Ruddle, 1665

Collected in: Accredited Ghost Stories, ed. T.M. Jarvis, Esq. London: J. Andrews, 1823

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

The Living:

Sila's Flood, 36. Minister and army chaplain (former). Writer.

Thaddeus Lynch, 29. Physical medium and owner of the Yellow House.

Ambrose Lynch, 24. His brother. A trance medium.

John Turner, 34. Cousin to Thaddeus and Ambrose.

Mrs. Ethel Ambler née Carr, 62. Widow of Dr. Quentin Ambler.

Friedrich Bauer, 35. Music teacher and violist.

Greta Bauer, 29. His wife. A cellist.

Sarah “Sally” Lynch, 19.

The Dead:

Katherine “Kitty” Flood. Wife to Silas. d. 1864.

Mary Lynch née Turner. Mother to Thaddeus and Ambrose. d. 1870.

Jeremiah Lynch. Her husband. d. 18??

Abijah Turner. Brother to Mary Lynch. d. 1859.

Joanna Lynch. Stillborn, 1841.

Jeremiah Lynch (Jr). Died in infancy, 1842.

Rebecca Lynch. Sister to Thaddeus and Ambrose. Diarist. d. 1855.

Johannes Bauer. First son of Friedrich and Greta Bauer. d. 1871.

Martin Bauer. Second son of Friedrich and Greta Bauer. d. 1871.

The children. d. 1832, d. 1864.

The Spirits:

Spring Willow. An Abenaki girl.

Evening Star. An Abenaki girl.

Chogan. A Pequot brave.

An old nurse.

A wounded soldier.

Two boys.

Father.

The train has stopped. The car sways and settles, dust stirred up and swimming in the air between our faces. We are south of Rutland, miles from any station. Rocky pasture is visible to our right, swaths of scrubland bounded by fences and fringed with cattle grazing in the shelter of the tree line: maples in late summer leaf, the day’s heat full upon them.

The spell is broken. An infant cries out, frightened, and its mother hastens to make the usual soothing noises. The child’s father uncrosses his legs and retrieves his paper from the floor, The Sun. He hides his face behind it.

An aging woman occupies the bench in front of me, her spinster daughter seated beside her. The older woman adjusts her crinoline and skirts, the peacock feather in her hat.

She says: “A cow, no doubt. Some poor beast driven onto the rails.”

“But surely, Mother, there is a cowcatcher?”

“You’re quite right. Perhaps we’ve struck the drover.”

“Mother!”

My notebook is gone. I notice its absence then fumble at the pockets of my waistcoat, turning them inside-out in my panic before the soldier seated opposite me clears his throat and offers it to me across the aisle. He holds the book with one hand, his left, as the other terminates at the elbow, the sleeve pinned back.

The two of us had exchanged greetings upon boarding in New York. Afterward, we lapsed into a kind of intimacy once it became apparent we had both served under Grant in the spring of ’64 and that we had, somehow, survived.

The notebook appears undamaged, though it must have flown across the aisle, and my notes are likewise intact. Loose pages are folded into quarters and thrust between the pages, witness reports or transcriptions thereof, firsthand accounts of the Lynch brothers’ purported mediumship: lurid tales of ghostly music, spectral voices, the spirits of loved ones conjured up bodily from the depths of the Spirit Cabinet.

T

he soldier says: “This, too, is yours, I think.”

And hands me a copy of The Sunday Echo. It is today’s edition, purchased on the platform in New York.

I thank him, but he only shrugs and extracts a pipe from his waistcoat then clamps the stem between his teeth. He strikes a match against the side of the bench and the flame leaps up to drink the unsettled air.

Behind him, two sisters (one married, one not) fall to muttering their disapproval. Presently one of the sisters speaks up. She is pretty and slim with her wedding band displayed prominently upon her finger.

“Excuse me,” she says. “Sir?”

The soldier ignores her or else pretends to deafness and sets the shag alight.

The second sister—older, her aquiline features marred by a bluish birthmark—rises from her perch and opens the window.

Everything motionless: no wind in the trees, no scrap of cloud on the horizon. The August dampness seeps into the coach, fragrant with greenery, the acrid tang of coal smoke from the engine.

We hear screaming, a woman’s. She howls like a wounded animal, her voice made ragged with anguish and the fever of dying while men are shouting to be heard. The commotion emanates from the front of the train and we realize at once what must have happened.

A woman on the line. A suicide, probably: she screams as the life drains out of her. I imagine it all, see her dragged along in the cowcatcher during all those long minutes in which the train screeched and shook.

The older sister shuts the window.

The woman’s screams remain audible, if somewhat muted, and the other passengers have no choice but to speak over them, which they do. Some discuss the heat (unseasonable, they agree, for summer’s end) while the baby’s father at the back of the car reads aloud from The Sun, the financial pages—and still the screaming will not be silenced.

Opposite me the maimed soldier drags on his meerschaum, obscuring his face with a web of smoke and glowing dust. He is listening, thinking, perhaps, as I am of nightfall in the Wilderness when the screams rose and swooped from the dark and the fires eddied through the trees, consuming the wounded where they lay and pleaded for water or death. Their cries from the roaring: Is that you, Reverend? Can your God give aught to one like me?

I press my hands to my face, digging in the heels so my vision sparks and flickers under the lids, wind and flames dissolving with the rush of blood that fills the opening eye: gold light in the coach, glimmering on the dust as it settles.

The screaming is gone.

The door to the forward car opens and the brakeman enters with his uniform in disarray: jacket and cap removed, shirtsleeves rolled to the elbows. He is pale, unsteady on his feet, and his voice burrs and quavers as he speaks.

“Is there a minister here? A priest?”

I say nothing. It is ten years since last I wore the chaplain’s collar and longer still since I have prayed—and though I feel his gaze upon me I do not speak or stand and at last he passes through to the next car, where we hear him make the same request.

The older sister speaks. “The worst has happened, I fear.”

“Has it?” the younger replies.

“He did not ask for a doctor.”

“Oh.”

We wait. Beyond the window cattle graze in the cool of the maple trees, the cropped grass glinting with the sun in amongst it. Gnats gather in clouds over steaming pools where rainwater brims in old wagon ruts, and the brakeman returns, at last, alone.

The soldier finishes his pipe. He looks at me, a little curiously, no doubt recalling our earlier conversation when I had said I was an army chaplain, but makes no comment. Behind him the two sisters don pince-nez (matching pairs, for all their other differences) and proceed to read from nearly identical books, successive volumes from a set of Dickens.

The Sunday Echo is in my lap, my name visible near the fold, printed in small type alongside the first of my two articles on the mediums Thaddeus and Ambrose Lynch. The second piece will appear in a week’s time after I have completed my investigation at their farmhouse in Moriah, Vermont. I am promised lodgings there, expected tonight, but Moriah is ten miles beyond Rutland and far from the rail-line, and I doubt I will arrive before morning.

I close my eyes, try to sleep. The baby cries out, a piercing wail. A rustle of paper as its father shelters behind The Sun, followed by a gentle music as the mother begins to sing. I listen. I cannot make out the words, but the tune is familiar enough.

Little Musgrave. Kitty’s favourite.

An hour passes, more. We hear a whistle from the south: screeching, drawing near. The din reverberates all around us, swimming out of the heat then slow to fade from the clotted air.

Movement from the forward car.

The door shoots back, admitting the train’s conductor. He is a greying man in his forties, tired, leaking sweat through the fabric of his uniform. He leads a column of overdressed men in damp jackets and women sprouting skirts and bustles who fan themselves with newspapers or novels or whatever is near to hand.

The conductor says: “We are changing trains.”

He sounds exhausted, beaten. He continues: “If you’ll please to follow me, we can walk down together to meet it. You should arrive in Rutland round about suppertime.”

A furious whispering ensues as the conductor limps toward us. The woman with the peacock feather stands, indignant, and clears her throat despite her daughter’s protests.

She says: “Now that’s all very well, but what of our luggage? This carpetbag is new, you understand, a gift from my dear brother—”

“Please, ma’am. Everything will be sent on to Rutland. You may collect your bags there.”

“I shall have them now, thank you.”

The conductor ignores her request and continues down the aisle, passing us where we sit, trailed by a procession of men and women, perfume and sweat.

“Please,” he says again. “If you would follow me.”

I slip my notebook into my pocket and stand, leaving The Sunday Echo on the seat. Across the aisle the soldier rises with the aid of a walking stick, while the two sisters clutch their books to their breasts and watch without expression as the others pass them by. The woman in the peacock hat is last among us to join the procession, and only grudgingly, after much coaxing.

We follow the conductor through each of the cars in turn until we reach the final passenger coach where we alight onto the southbound track some distance from our stalled locomotive. The engine is quiet, a wisp of steam clinging to the stack. Wagons and carts are assembled on either side of the rails, horses stamping idly amidst the shapes of men in dark coats.

The conductor hurries us along. His sole object, it seems, is to spirit us far from the scene of the incident, which he does. It’s nearly dusk, but the sun beats down despite the lateness of the hour, blurring the ridgelines to either side of us and mixing the trees with their shadows, the stains beneath our feet: ruddy streaks on the rails where the engine braked and dragged the body on the ground.

No one else notices. The aging mother laments the loss of her new carpetbag while her daughter offers up some ineffectual words of comfort. The maimed soldier walks alongside me, his footfalls alternating with the crack of his stick against the ties. He does not speak but marches with face upturned and the black hair plastered to his pate, sweat sliding free in rivulets.

Just ahead of us are two young men attired in the costume of Wall Street speculators: silk tie and waistcoat, top hat. They talk too loudly, their cufflinks shining.

“A suicide, I expect.”

“Yes.”

“The silly girl. Probably unlucky in love.”

“There will be a hearing?”

“Yes, but we needn’t attend. The conductor said as much.”

“Thank Christ for that.”

The landscape shifts then slopes away. We see the second engine waiting for us at the foot of the hill, faced north upon the southbound track with black breath pouring from it. The con

ductor ushers us aboard.

There are only two passenger cars, so I find myself sharing a bench with the former soldier, who smells faintly of gin and camphor. He wastes no time in lighting a second pipe, ignoring the pointed sniffs of the two sisters now sitting across the aisle.

The conductor confers with the train’s brakeman at the front of the coach. They exchange some whispered words and the brakeman nods, grimly. The conductor tips his cap and descends.

I watch him go.

He moves slowly, favouring his right leg (an old wound?), head bowed as he strikes north along the rails. The whistle bleats once then twice to clear the track ahead. The conductor vanishes over the rise even as the engine lurches into motion, lumbering uphill, gathering speed as we crest the ridge and push toward the other train.

A voice says: “Don’t look.”

It is the woman in the peacock hat. She is speaking to her daughter.

There are horses, carts, officials in dark uniforms. A hospital wagon standing empty. Two men in undershirts walk with a stretcher held between them and a humped shape laid upon it, draped in a horse blanket and mottled with dark stains.

The body is small, no bigger than a child’s. A young woman shuffles along behind the stretcher, dazed and with her best dress soaked through, black flecks clinging to the sleeves. The mother. Her eyes are empty, set like stones in her skull, and she isn’t screaming anymore. She follows the men toward the wagon, seeing nothing for the brightness that surrounds them, last light, her child’s blood splashed across a horse blanket.

We are past it. So quickly it recedes: steaming horses, sun-drenched countryside. A child cut to pieces beneath a train.

The soldier extinguishes his pipe and folds his arms over his breast. His breathing comes slowly, slumberingly, and I look to my right, where the tree branches shed their flickering light, the white glow dimming to blue then purple as we steam toward Rutland.

Soon the coach is dark but for a single lamp, looped through a handle near the forward car. It rocks in place with the humming of the rails, casting a cone of shadow between the windows to right side and left, teasing out my reflection then annihilating it altogether.

Among the Lilies

Among the Lilies The Lord Came at Twilight

The Lord Came at Twilight Moriah

Moriah